One of the most interesting aspects of restoring Green Farm for me has been learning about the fascinating history of the site. This is something that wouldn’t have interested 'teenage Dom' one bit – I hated history at school and dropped the subject as soon as I could. We only ever seemed to learn about the British monarchy; if only someone could’ve dropped in a bit of landscape history or archaeology instead, I might’ve paid more attention!

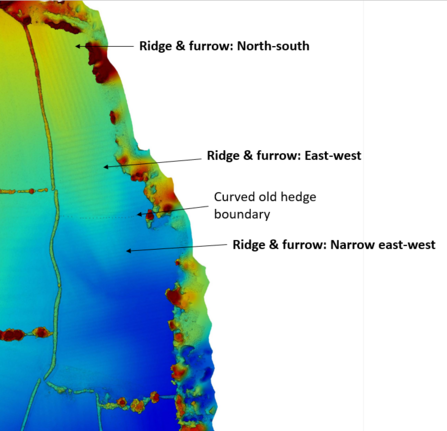

My newly found interest started with a winter walk across Green Farm in 2021. I’d been told that the landscape is easiest to read in the winter when everything is in stark silhouette, the sun comes in at a low angle to highlight raised features and the grass has been grazed low, making any bumps and dips more obvious. So on a sunny day in February, I went exploring for anything that looked unusual, mysterious and random in the context of the site as it is now. It takes time to get your eye in but after a while, things start to reveal themselves. Could that shallow bowl have once been a pond fringed with water mint and dancing damselflies above? Why is there a shallow trench that stretches all the way across Bullocks Ground? And why is there ridge and furrow going in different directions in Long Meadow?