As conservation trainees, reserves team leader Rob encourages us all to take on our own “project”. After several experiences of GIS (Geographical Information Systems) and coming from a technological background in a previous life, I decided to use the traineeship to expand my knowledge of GIS, which has become an increasingly important tool in recording and monitoring species and habitats on nature reserves and the wider countryside.

"What is 'GIS'?" I hear you ask! GIS is software that allows us to add multiple layers of information on to a base map. The three most common types of layers are:

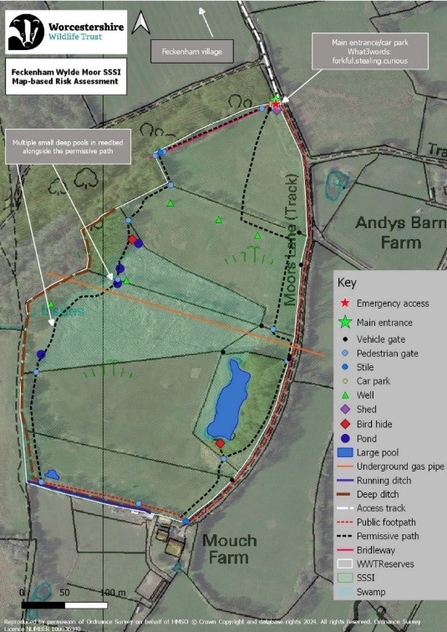

- Point layers - these refer to single-point features such as trees, buildings, gates or points where a particular species was recorded

- Line layers – these are linear features such as hedges, rivers or footpaths

- Polygon layers – these are used for complex shapes such as areas of habitat, or reserve boundaries

Each layer is associated with a table of data. For example, if I add a point layer showing the position of trees, each line of data represents an individual tree and the columns contain information such as species, date surveyed, girth and OS Grid Reference. To help identify different points at a glance, the software then allows the colour or shape of the points to change according to the data, so an oak could be green and an ash could be red - however, the possibilities are almost endless. Equally, the tables can be exported to an Excel spreadsheet for further analysis. That’s probably enough technicalities for now!